How Venezuela’s Good Citizens Were Disarmed is a Lesson For Us

The Venezuelan government publicly destroying confiscated guns in 2012

When I was a little girl in the early 1990s, my father worked in the energy industry and often flitted off to South America. He brought us back postcards and chucherías from this faraway land of Venezuela, describing it as the most picturesque nation in Latin America. The nation was then awash in oil wealth, the highest growth rate in the region, boundless education opportunities, fine foods and world-class beaches.

It seemed a mystical paradise where nothing could go wrong. Until it did.

When I stepped foot into the embattled nation a year ago to cover the burgeoning humanitarian crisis, none of my experience in war zones prepared me for the calamity that seemed to get worse with every step across the Colombian border. Venezuela had sunk into a violent humanitarian crisis. There was next to no rule of law.

The haunting images of desperate women chopping off their luscious hair in order to sell it for a few dollars, of mothers bottling their breast-milk to barter to other women so malnourished they couldn’t produce their own and the chilling sights of females as young as 14 years old selling their precious bodies unfurled around me.

Cúcuta, a city straddling the Colombian and Venezuelan border, had become the stuff of nightmares: a microcosm of the conflict burning Venezuela alive. Its citizens had become unable to defend themselves or their families from danger and economic ruin.

And the Venezuelans are the first to tell you that so many of them willfully surrendered their right to bear arms in the lead-up to the 2014 crackdown. They told me this as clear words of warning.

“Venezuela is paying the price for the gun ban. The civilians are unable to defend themselves from criminal actors and from this Maduro regime’s abuses,” activist and university teacher, Miguel Mandrade, 34, said from the fog-laden, barren city of San Cristobal. “The uprising would have taken a different path and a different result if civilians had the right to defend themselves with the firearms they once owned.”

Each morning, as the sun rose over the tropical plains now dotted with homeless people and trash, I would sit by the jagged border crossing and watch as thousands flooded into Colombia from Venezuela carrying everything they owned in little backpacks, their feet swollen and shoes broken from the days and weeks of walking. It was a sight that was hard to digest.

Some 4 million have fled the profoundly impoverished nation that, as this was being written, was still led by socialist dictator Nicolás Maduro. Meanwhile, the millions left languishing inside Venezuela’s borders are starving and without critical services and medical care. Homicide and crime rates are escalating as the inflation rate soars. The government has unleashed its forces and proxy militias to wage war on a troubled and defenseless population.

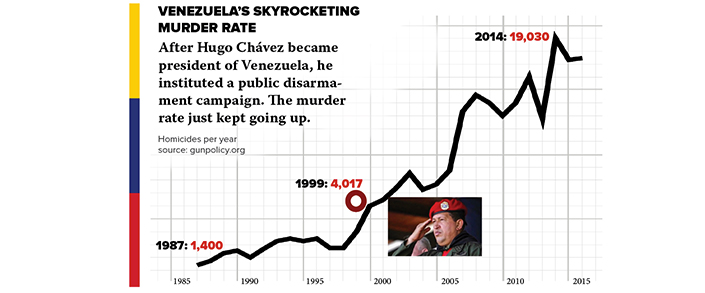

But the trigger of gun prohibition wasn’t pulled in an instant. Over several years, Venezuelan authorities chipped away at individual gun rights.As they did so, crime rates crept higher and higher.

The following year, Caracas banned the commercial sales of guns and shuttered the doors of firearms stores across the country. It was mandated that only military, police and security forces could legally own and buy guns.

Then, in 2012, Maduro signed into law the Disarmament and Arms Munitions Control, which carried the explicit objective to “disarm all citizens.” Chávez initially ran a months-long amnesty program urging Venezuelans to swap their arms for electrical goods; however, only 37 surrenders were recorded, while more than 12,500 guns were seized by force.

The government held grandiose decimation displays in the streets by bulldozing firearms en masse in front of large crowds in a bid to demonstrate their commitment to supposedly end gun violence.

In 2014, a further 26,000 firearms were confiscated or crushed—coincidentally, Venezuela clocked in as having the world’s second-highest homicide rate that very same year. Each year that the gun-control reins were pulled tighter, murder rates increased.

In 2001, according to gunpolicy.org, 6,568 homicides were recorded in Venezuela. By 2014, that number had jumped to 19,030.

Not-so-coincidentally, the black market in weapons also began to boom, with an estimated 6 million illegal guns in the country.

“The market works through international borders, in maritime and land areas, and the government itself has been a gun provider,” said Walter Márquez, a Venezuelan historian and former National Assembly Representative. “The government took legal weapons away from private people, disarming all those who could oppose it.”

The seller, a man with bloodshot eyes who offered no name, explained that handguns start at around $250 and rifles around $500. As I heard these prices, I knew that the overwhelming majority of the Venezuelan population is lucky to receive a few dollars a month in their socialist government stipend.

Even the black market is run by corrupt government officials who exploit their positions of authority. They access contraband items and sell them at high prices to those who can pay. I learned all this through my intermediaries who watched day after day as those appointed to the government found ways to profit off their positions.

“Not surprisingly, the individuals with the funds to purchase weapons are usually narco-traffickers or other bad actors; however, the black market is also used by many expat Venezuelans who want to purchase food and medicine for their families,” said Ephraim Mattos, executive director of Stronghold Rescue & Relief, which issues humanitarian aid to fleeing Venezuelans. “These expats earn money in other countries and illegally send the money to government officials in Venezuela who then deliver the goods to the expat’s family.”

He pointed out that the very same firearms which were turned over by the law-abiding citizens to the government in the so-called buy-back schemes have, in turn, been given to government-sponsored armed groups that now directly oppress the law-abiding citizens who turned in their guns.

The most egregious offenders are known as the “colectivos,” or collectives. They are armed by Caracas and deemed vital to Maduro’s survival. The collectives ruthlessly oppress opposition groups, giving Maduro a cosmetic cover.

When we saw them, we ran for cover. When a few learned that we had crossed the fragile border without paying off the number of people we were supposed to, they chased us through the thick crowds of fleeing people. A few heart-in-throat moments later, after a panicked exchange between my interpreter and the half-masked men, I was instructed to leave the area.

I was one of the lucky ones.

“Venezuelans will often travel to neighboring countries with valuables to sell, such as jewelry and electronics,” Mattos said. “The colectivos will stop the travelers at random and steal those items—women are often raped during these stops as well.”

“At the border, the colectivos usually charge a tax to cross as well,” he continued. “The Venezuelan people are suffering for the simple mistake of giving up their ability to protect themselves from a socialist government. They willingly invited the enemy into their own home. The destruction of the country was not the sudden result of an armed overtake of the government, but rather it was the insidious lies that slowly crept in and infected the country.”

Chavez, Maduro’s predecessor, was democratically elected by the Venezuelan people, and he is the one who began the process of socializing the Venezuelan economy.

“The Venezuelan population trusted the government at all times that it would always use its authority within certain boundaries, and whenever it got out, we thought it would be solved by democratic or legal mechanisms. Our political and public behavior confirmed our cultural naivety in this sense,” said Javier Vanegas, 29, a Venezuelan teacher. “We are paying the price of not having had a strong gun culture.”

Before the 2012 changes, there were only eight registered gun stores scattered across the nation of 31 million people. The process for law-abiding citizens even to obtain a legal gun permit and a firearm was a months-long ordeal hamstrung by protracted wait lines, high costs and demands for bribes. Only one department, which operated under the Ministry of Defense, had the authority to issue civilian permits.

The collectives ruthlessly oppress opposition groups, giving Maduro a cosmetic cover. When we saw them, we ran for cover.

In late 2017, when Venezuela was in the clutches of its spiraling economic catastrophe, Maduro announced he would distribute some 400,000 arms to his patriots—claiming a U.S.-led coup was coming—and the civilian population was left as sitting ducks. Since April of that year, hundreds of Venezuelans protesting the government, armed with little more than stones and paper signs, have been shot or have disappeared in retaliation.

“If citizens had access to guns, and if they had been armed since before the arrival of Chavez, it would have been, at least, a powerful obstacle to the socialist agenda,” said Vanegas. “Socialism thrives in chaos. The perfect tool for chaos in most of Latin-America is criminality. If the people had had the tool to defend themselves, instead of resorting to more state power to end the criminality (an end the government never intended to give), then, of course, it would have made a huge difference.”

In recent years, he said, the daily life of the unarmed Venezuelan has been shaped by crime.

“People have stopped going out. Businesses and businessmen and women went broke or closed shop and left. The youth began to be fearful of spending time out in the city,” Vanegas said. “I personally had one family member and two friends kidnapped for ransom.”

The stuff of nightmares quickly became normal to the likes of Vanegas, who reflected that his complacency has been shattered as his beloved country has fallen apart. Scores of ailing Venezuelans told me that even before the protests sparked five years ago, calling the police to report a crime entailed long wait times and pressure to bribe officers not only to come, but to process the case per the book. Now, even making such a call is basically useless.

One person I met on my travels in the region whispered in hushed tones that those who dare keep an old gun beneath their bed—or those who have the finances to find one on the black market—risk the punishment of 20 years behind bars. This person confessed that he kept an old revolver that once belonged to his grandfather. He worried that if he used it to save his own life, the Maduro regime would then come to take him away to prison.